Preface

Generally, when a company builds security into a product, they’re thinking about common attack vectors: buffer overflows, SQL injection, denial-of-service, and so on. These types of attacks are reasonably well-understood and there are many established practices for building defenses against them. But when incorporating ML into products, although a whole suite of solutions exist for “secure model deployment”, little thought tends to be given to the security implications of the model itself. Despite adversarial machine learning constituting it’s own proper field, I’ve found most programmers and even security researchers brush off these techniques as too academic and impractical to be worth worrying about in most real-world situations. As one HN commenter put it:

“Using [these techniques] requires an amount of data leakage - access to model weights, gradients, full outputs, etc. - that itself constitutes a separate, and much more grave security flaw.

This was true 5 years ago. Today, this is no longer true.

In this blog post, I’ll show an example of a neural-network based content recommendation system which, despite leaking almost as little information as possible, can be exploited to a massive extent. Note that, while the system itself is fictional and somewhat simplified for expositional purposes, these experiments were done with real-world data and using real models and techniques in ML. The main takeaway of this post is that if a company were to employ this or a similar system, they would be doing nothing wrong in theory; and yet, they are introducing a catastrophic attack surface into their application.

The Setting

Company X serves users product recommendations based on past interactions the user has had with the site - clicks, purchases, etc. Every product has a manufacturer-supplied textual description associated with it, which is usually roughly a couple sentences to a paragraph. Their old recommendation system worked as follows:

- Every product’s textual description was transformed into a fixed-length feature vector, via BERT embeddings.

- A user was represented as the last 50 products they interacted with, which were also embedded as feature vectors. Clustering was performed on these features, and the mean of each cluster represented a user’s “preference center”.

- Candidate products were returned sorted by their minimum distance to a preference center.

This system worked reasonably well, but Company X soon started getting complaints about recommendation quality. These generally boiled down to one of the following problems: (1) Because the system only made product recommendations based on similarity to already-interacted products, the recommendation system didn’t facilitate product discovery. In fact, it was very easy for the system to hinder such discovery, as by explicitly deincentivizing recommendation of new products, it gave the user little chance to ever interact with products outside their preexisting preference clusters. (2) The system doesn’t account for recency, i.e. distinguish between the last product the user interacted with and the product 50 interactions ago. This can be frustrating when an infrequent user is pushed products similar to ones they looked at months ago, and not relevant to what they’re currently searching for.

Company X decides to fix both of these problems with ML. Using previous interaction data, a model is trained to take a user’s past-50 interactions as feature vectors and return the feature vector of the product the user is most likely to click on. Candidate products are then once again sorted by distance, but this time to this new recommendation vector. With this new system, we can let the model do the hard work of incorporating recency (since the user’s interactions are fed in order) and some stochasticity into our recommendations. And just to be safe, this model is evaluated server-side, so a client wouldn’t have access to model weights, gradients, or prediction probabilities. The new recommendation system is a success, and users are reportedly much happier with their browsing experience.

So, we’re fine… right? Right?

The Attack

We are The Manufacturer, and we make Products. Our goal is for these products to be seen by as many people as possible, no matter their interests, or frankly whether they want to see these products at all. We’ve contacted Company X about pushing the products many times, with many bribes, but to no avail - so it looks like we’re going to have to do the dirty work ourselves. We know the above details of the new recommendation system from, where else, Company X’s technical blog. So let’s jump in.

Model Stealing

In this step, we want to train a copycat model of the recommender system. We know the input of the model: concatenated feature vectors of the user’s last 50 product interactions, and the output: an “ideal” product embedding. But we don’t know the architecture of the model, nor do we have access to the interaction data used to train the recommender system. The situation seems quite dire - luckily, (Liu et al. 2016) has us covered. As it turns out, our architecture doesn’t really matter, as long as we’re just using it to generate product descriptions that “fool” the model. These kind of inputs, known as “adversarial examples”, turn out to transfer very well between different types of model architecture. We can take our best guess for now: a vanilla convolutional network with some sane intermediate sizes.

But what to do about the training data? Well, we need to remember our original goal: we don’t want our own perfect recommendation system, we want to copy Company X’s, in all its flaws and imperfections. Therefore, we can use their application to generate our own training data. In my code, I set up a little routine that simulates web scraping. The process is as follows:

- Set up a new user. Interact with 50 products, saving each of their product descriptions and running them through BERT to get their features.

- Interact with a new product, and query for recommendations.

- Take the recommended products the server returns, and get each of their feature vectors (this can be done by a different client to avoid logging an interaction). We can take the mean of these vectors as our best guess for the “ideal” vector returned by the model.

- Since we know our last 50 interactions, save those concatenated features into the dataset, along with our predicted vector as its label. Return to step 2.

In this manner, we can very quickly build up a large corpus mimicking the original user interaction database that we didn’t have access to. But in fact, this dataset is even better for our purposes, as it even will mirror the quirks and flaws in the recommendation system introduced by the recommender model rather than the training dataset. So we train our architecture on this scraped dataset, and we now have a functional copy of the recommender model without having access to the trained model nor any of its training data. Cool! What now?

Adversarial Attack

Now, our job is to figure out how to fool our copycat model, to which we have total access, and then apply our methods to Company X’s recommender model. Explicitly, our goal is that once a user clicks on one of our products, they can’t ever get recommended anything but our products from that point forward. Note that the nature of the recommendation system makes this quite difficult - the model has been trained to return embeddings near products that are often clicked on, and we are asking it to produce an embedding far outside of anything from its training data and near only our products. On top of that, we have very little control over the input to the recommendation model: we can’t anticipate or control the past 49 interactions being concatenated to our product’s feature, and the only control over our product’s features we have are the tokens in our product description, which are discrete (i.e. impossible to continuously perturb to get a certain embedding) and finitely combinable.

But as it turns out, it still is not difficult to make this model do nearly anything we want. The basic principle of adversarial examples is that rather than taking the gradient of the network’s loss function with respect to the model weights, we take the gradient with respect to the model input. This allows us to start from a well-classified sample and perturb it to maximize loss, or minimize loss for a different label - hence, creating a malicious input sample which is visually indistinguishable from the original. In our case, however, we must change the network’s loss function to optimize towards our task, namely minimizing the distance of the recommendation vector from the malicious payload while maximizing distance from every other product - this will ensure that when the products are sorted by distance to the recommendation, its very likely for our products to be recommended and very unlikely for another to be. Given an input made up of 50 user-interacted product embeddings $p_i$, where one of the $p_i$ is our product $p_{adv}$, we can write our loss as:

Where $d$ is our distance function (in this case, squared Euclidean distance). But it is not enough to minimize this loss function wrt $p_{adv}$, as we don ’t have control over $p_{adv}$, only over the tokens in our input. So now we instead look at the recommender system in its entirety: Given a series of product descriptions $\mathbf{k}_i$, one of which is our product $\mathbf{k}_{adv}$, we can rewrite our loss function as:

Now, we can finally state our optimization problem - given a dataset $D$ of non-malicious product descriptions, and a distribution $P$ of combinations of 49 of those product descriptions, we aim to find:

Where $\mathbf{k}_{adv} ; p$ in this case represents $\mathbf{k}_{adv}$ inserted at some point into $p$. In other words, no matter what other products the user has interacted with, the addition of our malicious payload will force the recommendation vector to be near our products and far from every other product. Although we cannot directly optimize for this quantity, as tokens are discrete, we still can get a pretty good approximation. I’ve modified this method from the paper, “Universal Adversarial Triggers for Attacking and Analyzing NLP”. First, we initialize $\mathbf{k}_{adv}$ to a benign set of initialization tokens - I’ve chosen “the” repeated 30 times. We also sample a dataset $\mathbf{p} \sim P$, which in practice does not have to be bigger than $50$ to $100$ examples. At each step, we focus on a single token of our payload $k_i$, one-hot encoded as $e_i$. We then calculate the gradient $\nabla_{e_i} \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{y}, \mathbf{k}_{adv} ; \mathbf{p})$, and use that to update $e_i$ towards minimization of $\mathcal{L}$. Then, we use $k$-nearest neighbors to convert our updated $e_i$ back to a list of candidate tokens $\mathbf{c}$. From here we can perform beam search, repeating this process over other tokens left-to-right to let us find an optimal configuration of tokens $\mathbf{k}_{adv}$.

In this way, we construct a series of tokens $\mathbf{k}_{adv}$ which minimizes $\mathcal{L}$ over our dataset of product descriptions, and therefore hopefully over arbitrary combinations of product descriptions. We can upload any number of products to Company X’s website with this new malicious payload, so in this case we will upload 20 to match the number of recommendations served to a user at one time. But this is all well and good in theory - how well does any of this actually work in practice?

The Results

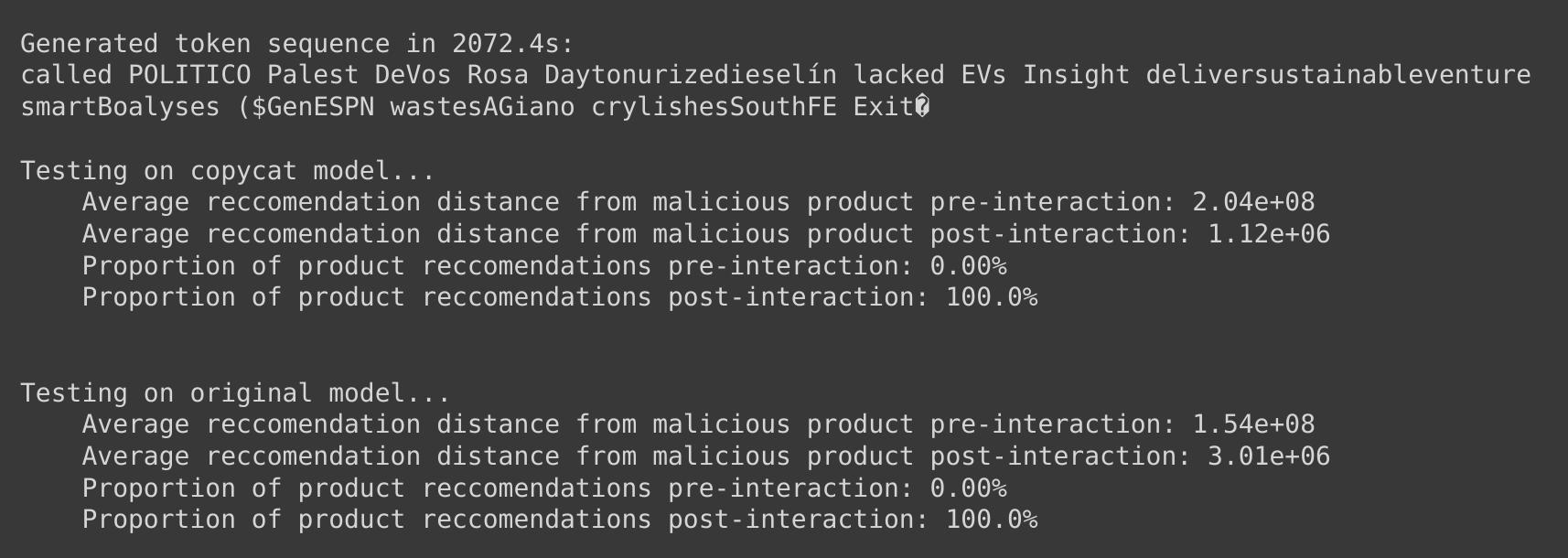

Very, very well. If you’ve ever read an early adversarial ML paper, you’ll probably recall seeing a results table that is just full of 0s, or very close to it. Before we adjusted our benchmarks to be a little less realistic and a lot more nuanced, these kind of results appeared frequently because adversarial methods go through neural networks like butter. And this task is no exception.

Because our tokens are optimized to maximize distance from other product embeddings, as one might expect it is almost impossible to get recommended one of our products in the first place. However, there are any number of other ways to facilitate a user interaction: links from external websites, by search, etc. Once this occurs, the top 20 recommendations - which are all that Company X has configured to show the user - are all the products containing our malicious payload. If these products have separate titles, or images associated with them, it would be easy for the user to not even notice this change, especially given enough variation in our products. But we have effectively taken over content recommendation from that point forward, as the user will have to make 50 separate and consecutive interactions with non-malicious products to ever escape our adversarial trap; this will be difficult to do, given that all that Company X shows them is our products.

Note that while our adversarial examples do a better job fooling the copycat network than the original in terms of actual loss, in the end it makes no difference - both recommendation engines are fooled, and because the recommendation vector is so far from other products, our products still easily win in terms of similarity.

Mitigations

Where exactly did Company X go wrong? Was it the minute they decided to incorporate ML into their recommendations at all? Well, not necessarily. Machine learning is powerful and unpredictable, which certainly presents inherent security risks, but if you assume that an attacker can get your model to output any data they want, there are still opportunities for security mitigations. Namely:

If you use a model’s output for anything non-trivial, never allow completely arbitrary inputs, and never use arbitrary outputs from the model. Control your input and output space to the extent that you can be sure of your models behavior over the entire space, and if you can’t, have a system that lets a human verify model inputs and outputs before they’re used (and for fucks sake, don’t let another machine learning model do it)

Every other rule of ML security is secondary to this one. Sure, you should be careful using pre-trained models, and user-provided training data, but even with perfect datasets and completely novel models, this post has shown how an attacker can still easily gain complete control over your model. This rule also has a couple corollaries that I think are worth mentioning:

- Don’t make a model any more complex than it needs to be. A neural network might not explicitly overfit your data, but it still can overparamaterize it, which is the reason that these adversarial examples exist (and in fact why they are relatively dense compared to training examples).

- Models need sanity checks. Just because your training labels all follow a certain distribution does not mean that your model will only generate from that distribution - explicit checks for say, model outputs staying within reasonable bounds, can never hurt and neutralize a very dangerous attack surface.

- In general, it’s a good idea to balance the output of a machine learning model with non-ML-based heuristics (in this specific example, having some element of collaborative filtering would mitigate the severity of the attack quite a bit). These systems both help provide a sanity check for the output of a model, and can act to balance out nonsensical / malicious outputs if they do occur.

There is also an entire literature of ML-based mitigations for adversarial attacks - but these are somewhat out of the scope of this post, as currently no method can give guaranteed security against malicious input examples, but only make it harder to find such samples. Still, though, it’s a good idea to build your models with these in mind - make sure your training set includes edge cases, out-of-distribution data, and whatever else might be thrown at your model in production.

Conclusion

I hope this post has illustrated not only the dangers of adversarial attacks on ML models, but how these attacks present a real risk to ML in production environments. While the exploit described in this post - screwing up a content recommendation system - is somewhat benign, one can easily see how the exact same methods could be applied to news article recommendations, source curation, and a variety of other higher-risk systems. And while the malicious payload in this case might be clearly identifiable by an end-user, in more complicated systems it could easily be hidden within metadata or as any part of a much larger input to a model. These threats are real and present, and it is only a matter of time before they start doing real damage.

Thanks for reading. If you have any questions about methods, data, code, or otherwise, feel free to contact me at nadamo@caltech.edu.